- Home

- Richard Purtill

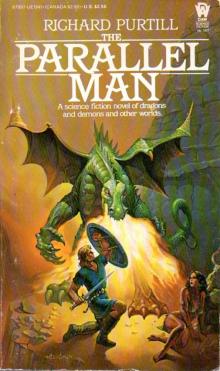

The Parallel Man

The Parallel Man Read online

The Parallel Man

Richard Purthill

A science fiction novel of dragons

and demons and other worlds.

“Can it be that all this is just some sort of spell cast over me the last two years, when Mortifer came with his warning of the firedrakes? I never trusted him. What did he do, kidnap me and imprison me here? The kingdom. . . my father . . are they. . . ?“

I swallowed a lump in my throat and faltered. “In some of the old tales they say that men taken under the hills by the elvish folk have returned to find their friends grown old or dead; that a year with them under the hills is many years in the world of mortals. Is it something like that?”

Droste’s eyes met mine as he said, “As nearly as we can tell from the time of your last genuine memory until now is about five hundred years.”

THE PARALLEL MAN

Being a clone can certainly have its advantages. For one thing, it’s unlikely that someone would go to the trouble to clone the average Joe on the street; more likely one would seek to duplicate a brilliant statesman, a scientific genius, a famous poet, or perhaps a legendary king....

But then again, being a clone can certainly have its problems. If someone sought to replicate a powerful person from history it wouldn’t be without a reason. There could be scores of Napoleons, dozens of Julius Caesars. . . But if it was an evil sorcerer who cloned you, and you didn’t know his motives, you could be the focal point of disaster.

Prince Casmir thought his life was challenging enough as it was, but when he discovered the truth about himself, battling firedrakes seemed like child’s play, and his life opened like a horrible Pandora’s box. For once the secret was out, there was no end to the dangers which double-shadowed his every move!

RICHARD PURTILL

in DAW Books:

THE GOLDEN GRYPHON FEATHER

THE STOLEN GODDESS

THE MIRROR OF HELEN

THE PARALLEL MAN

Copyright ©, 1984, by Richard Purtill

All Rights Reserved.

Cover art by Ken W. Kelly.

DAW Collectors’ Book No. 587

First Printing, July 1984

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

Part I

1. Beyond the Broken Sky

The firedrake screamed as it swooped at me again. I lifted my shield and felt the blistering heat on my shield arm as the fiery blast of the creature’s breath flared out. After a moment I dared to flick the shield aside and swing my sword with all my strength at one of the fiercely beating wings. The sword bit into the leathery membrane, but it was almost wrenched from my hand when the firedrake half folded its wings and dropped like a spent arrow into the abyss below us. I leaned back against the tree, letting my weary arms drop to my sides. There would be blessed moments of rest while the creature swooped even lower to build momentum, then spiraled upwards with beats of those mighty wings to where I stood on the ledge. The massive old tree protected me from a thunderbolt-like attack from above; the creature had to swoop by almost level with me, trying to burn or claw me.

Behind me I heard the clink of a chain as Princess Delora tried to move farther into the crevice which gave her a little shelter from the side-blast of the firedrake’s breath. I risked a quick glance over my shoulder. Her lovely face was grim as she met my eyes. She knew and I knew that no Champion had successfully defended a Sacrifice from the firedrake since the sacrifices had begun years ago. Worse yet, I, her defender, was the one they called the Afflicted Prince. If the Falling Sickness struck me now. . . .

1 didn’t dare to worry about that, or let myself think about what might happen if I lost consciousness as I leaned over the edge to see the firedrake’s position. It was flying a little awkwardly, I saw with a stab of hope, taking longer to fly up to the ledge than it had last time. If I could only injure that wing more the creature might not be able to fly strongly enough to make its way up to the ledge if it had to swoop down again. There would be more glory in killing it, but I would be content with a draw which would allow Delora and myself to spend the prescribed time on the ledge and be released with honor.

The firedrake was on a level with the ledge again but instead of swooping at me it banked, spilled air from its wings and landed at the other end of the ledge. Then it began to advance toward me with a shuffling motion of its hind legs. The wings were poised over its back and the forelegs with their vicious claws were making striking motions in the air. But the real danger was the writhing serpentine neck which could send the blunt head at me with the force of a battering ram; even without the wicked teeth in the gaping mouth or the fire that the creature could breathe, that head could knock me flat, my bones shattered. The tree would be no obstacle; the creature could strike around it from either side.

I stepped toward it along the ledge, my shield poised to ward off another fire blast, ready to leap back if the head darted toward me. If the creature could kill me or knock me off the ledge, nothing could prevent it from continuing its inexorable progress down the ledge to the crevice where Delora was chained and making a grisly feast on her helpless body.

The neck straightened, a sign that the creature was about to let loose another fiery breath, If I stood and took the blast on my shield, the firedrake could bound toward me and be on me before I could recover. With desperate invention, I hurled my shield at the gaping jaws and dived under the head toward the more vulnerable body. I heard my shield crunch as the firedrake instinctively snapped at it; then I was lunging for the creature’s heart with my extended sword.

The tip penetrated a hand’s breadth and then would go no farther. My feet scrabbled for purchase on the stony ledge, but the creature was wincing back, its fore claws trying to tear the sword from my grasp. I felt the hilt slipping from my sweat-slippery hand: in a moment, the creature would spit out the shield and I would face its jaws and its fire with neither sword nor shield. Only one thing to do: I let go of the sword and grasped the neck above me with both arms. I swung my legs up and wrapped them around the neck and with a desperate heave and pull got myself on top of the neck. I reached for my heavy dirk, tore it from its sheath and plunged it into the firedrake, above my head. Then using the dirk as an anchor, I heaved myself toward the creature’s head. The fiery breath whooshed out in a useless reflex. I was behind it now and hardly felt the heat, but a muffled cry from Delora told me that the crevice had not sheltered her from the blast.

Now I was straddling the neck, just behind the firedrake’s head. My dirk plunged into one of the creature’s eyes, stuck for a heartstopping instant, then came out. Now the other eye: the firedrake was blind. The worst moment was when I had to let go and drop from the monster’s neck; I almost froze to the false security it offered. But I was hardly on the ground before the firedrake battered its head against the mountainside, trying to knock off whatever had stung it so intolerably. I would have been smashed to a pulp, and still might be; I huddled in the angle between the ledge and the mountain wall that rose above it.

The firedrake shrieked again and again; the pain in my ears was excruciating. Gobbets of black oily blood spattered the ledge as its head thrashed back and forth. My sword was still stuck in its breast. Did I dare make a dash for it? If only the creature would blunder off the ledge. But no, it was going forward, toward Delora, extending its wings to guide itself by the pressure of the right wing against the mountain wall. Only one way to save Delora from the fiery blast that would surely come: I rolled toward the ledge’s rim and sprang up at the firedrake’s left wing, tearing at the leathery membrane with my dirk as I hung on the wing with all my weight.

The massive head came around toward me with the speed of a striking serpent, and that completed the ov

erbalancing I had hoped for. The firedrake began to topple from the ledge, carrying me with him. Delora was safe; as for me, perhaps the harpers would find another name than “Afflicted” to remember me by. Firedrake slayer: a good name to die with, if one must die.

Of course I cherished mad hopes; perhaps I could cushion my fall on the creature’s body or leap free into the trees below. But I think I would have died there—if the sky had not broken. Impossibly, fantastically, as I began to slide over the edge clinging to the firedrake’s wing, a jagged circle opened in the sky above me; shards of blue rained down from it. Beyond the circle was what looked like a gray corridor, as if the sky was a wall with a passage behind it. In the corridor, men in strange, skin-tight garments that covered all but hands and faces. Gods? Demons? But surely neither would show the blank amazement, the utter incomprehension with which they looked at me and at the firedrake.

A convulsive shudder by the firedrake sent us over the edge and we tumbled crazily as the creature beat its one sound wing in an effort to fly. Then something seized me like a giant invisible hand and the firedrake tumbled on below as I began to rise in the air toward that mad circle in the sky. A scream came from below: Delora’s nerve had cracked at last at this final insanity. My dirk was still in my hand and I brought it up with some instinctive thought of defending Delora or myself against the strangers. Concerned faces looking down at me from the hole in the sky suddenly became wary. One of the men pointed some stubby object at me; there was a strangely familiar purple flash and I lost consciousness.

I awoke in the strangest room I had ever been in. The walls and ceiling were the color of thick cream, featureless and smooth. One wall shone with a cold clear light and on one of the other walls an oval patch of colors moved in slowly swirling patterns. I was lying in a bed, covered with some sort of pale, clinging coverlet, feeling the sick shaken sensation that often came to me after an attack of the Falling Sickness. It often helped to get up and move around, so I tried to fling aside the coverlet to rise from the bed. The coverlet would not release me; it clung to the bed and to my body with firm but gentle persistence. There was no discomfort, but I was trapped in the bed: my blood began to pound and my headache grew worse as I struggled to get free.

As if in response a white circle appeared on the wall opposite the bed, the size of a shield and about head height. At first it was featureless, then suddenly a woman’s face appeared in it, not like a picture but solid and real, yet with nothing but the face visible, framed in a sort of white haze. The eyes looked as if they saw me. The face gave a small, impersonal smile and a soft voice said, “Someone will be with you in a moment.” Then the face vanished and the white circle faded.

I had no way to measure time, but the time that followed seemed to me longer than a “moment” by any reckoning. Finally a white rectangle, like a door, appeared on the wall. At first it was merely a shape of light, then suddenly it was an opening in the wall and people were walking through it into the room. One of them was the woman whose face I had seen. She was dressed in a skin-tight white garment that covered everything but her face and hands; around her waist was some sort of belt from which hung a number of small glittering objects. Somehow she reminded me of the chatelaine of a castle with her bunch of keys at her belt, though the glittering objects looked not at all like keys.

Beside her was a man dressed in a black garment which did not cover his head and seemed somewhat looser than the woman’s. There were touches of white at his neck and wrists and his thin, intense face was that of a scholar or a monk. Behind the man in black and the woman in white were two men in very similar garments, one in brown and one in gray. Something about the way the man in gray carried himself made me look more closely at him. He had the crude features and vacant look of a serf but instead of the usual shock of hair he seemed to be wearing a curious kind of skullcap of bright blue which covered his head to just above the eyebrows.

The man in brown was no serf; he did not have the intensity or authority of the man in black but he looked competent and responsible. He was pushing some sort of gray box in front of him; I blinked as I saw that it seemed to hang suspended in the air with no support. I did not want to face these strangers flat on my back; I tried to heave myself up and found that the bed changed its shape to support my back. I still felt at a disadvantage, confined as I was by the clinging coverlet, but at least I could face my visitors. I folded my arms and made my face impassive, waiting for them to make the first move.

The little group stopped at the foot of my bed and I suppressed a smile as I realized that it was they who were at a slight disadvantage; the bed was a high one and I looked down on them like a ruler from his chair of state. The man in black inclined his head gravely and said in a deep voice, “I am Justinian Droste, of the Citizens’ Liberties Union.” The title meant nothing to me; some sort of guild perhaps, though the man did not look like a merchant.

“I am Casmir,” I said shortly, “of Castle Thorn.” The gear they had taken from me would tell them that I was a knight of Thorn, if they had skill to read the markings, but it would be foolish to name myself as the Prince to men who might be enemies.

The man who had named himself Justinian Droste hesitated; he looked somehow unsure of himself; perhaps even embarrassed. “There are things which you will learn,” he said, “about the place you call Castlethorn.” He ran the name together as if he were unfamiliar with it, but that might be a deception. “That place is not what you believed it to be,” he went on, “and you have been used by others for purposes of their own. That is over now and I am here to safeguard your rights.”

I tried to keep irony out of my voice as I said, “I thank you for that, Ser Droste. Tell me then, since you are my guardian . . . am I a prisoner in this place or a guest?”

The woman in white broke in, “This is a hospital. You’re here because of some injuries you’ve suffered and for observation. When we’re sure that you’re able to function normally you’ll be discharged.” A hospital; the word was unfamiliar but perhaps it was a sort of hospice. A place of healing at any rate. The woman in her form-fitting white garment did not look like a sister of charity, though I supposed she must be something of the sort. I gave her what I could manage of a bow from my position in the bed and turned back to Droste.

“And then?” I asked.

“You will be quite free to do as you wish,” he said, a little too smoothly. “In fact one reason for our presence here is to formalize your rights.” He beckoned to the man in brown, who pushed the gray box to the right side of my bed. I looked closely at it; I had not been wrong, it did float in the air. “Please place your hand on the Register,” Droste said. The floating box was an uncanny object, but it would be unfitting to show fear before them; I placed my hand on the box without hesitation.

“Please give your name,” said the man in brown. I did hesitate then—was this some sort of oath taking? Their gray box meant nothing to me and I could not be oathbound just by saying my name.

“Casmir of Thorn,” I said and couldn’t completely conceal my start when a smooth neutral voice seemingly from within the box said “Casmir F. Thorn.” There was a tingle on my wrist and I took my hand from the box to find a green dot about as large as the tip of a finger glowing on my wrist. I picked at it and found that it was a thin patch of some smooth material which came away easily enough from the skin of my wrist, but then stuck to my fingers.

“Your citizenship and credit chip,” said Droste, “honored anywhere in the Universal Commonwealth. Wear it wherever on your body you like; most people find a wrist most convenient.” He pushed back the cuff to show a blue dot similar to my green one on the back of his left wrist.

The woman in white pulled away the hood which covered her hair and showed me a green dot on the lobe of her ear. “Move it around occasionally,” she said, “it can irritate the skin if it stays too long in one place.” I put the thing back on my wrist; there would be time to investigate it further when I was

alone. The woman in white turned to Droste. “We’d better go now,” she said. “The medication causes him to need considerable rest.” To me she said, “Try to relax and please don’t fight the clingsheet, as you were doing after you woke up. It’s there to keep you from injuring yourself while you’re healing, but we’ll have you out of it soon.” I sketched a bow again. It was irksome to be confined but I needed to know more before I took any action. She smiled politely but without warmth. “We’re short of human staff but I’m leaving the andro here for you. Tell him if you want anything.” The serf with the odd skullcap looked at me vacantly, then at a gesture from the woman went and stood near the opening through which the party had come into the room.

Droste inclined his head to me in his curiously formal way. “You must have many questions,” he said. “Be patient. They will all be answered.” He turned to go.

“There’s one question I’d like answered now,” I said. “Before I . . . woke up here . . . there was a woman with me; she may have been injured. Is she in this place too?”

Droste looked at me with an expression I could not read and said with curious gentleness, “No . . . no. We did not bring a woman from where we brought you, Casmir of Thorn.” He must have seen from my expression that I was not satisfied and he went on after a slight pause. “There was no woman with you when we found you. No woman at all.” Then he turned and left the room, followed by the woman and the man in brown. The doorway filled with white light which faded to show an apparently unbroken wall, as blank as the gaze of the blue-capped serf who stood against it.

The Parallel Man

The Parallel Man